Kid Considerations:

I Really Want to Like the Female

Lego™ Scientists, But....

Before I go

any further, let me just make one thing clear—I LOVE Legos! Even though they were available in this country by the

time I was born (and no, you don’t need to know exactly when that was...), they

hadn’t really “caught on” with wide distribution, so, in other words, I never had any as a kid. When I started

teaching (WAY back in the dark ages...1978, that is...), Lego was one of the

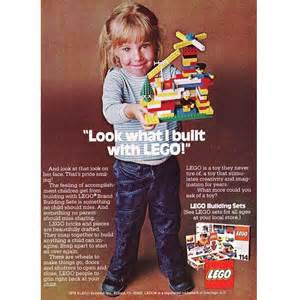

toys that fueled my second childhood. At that time, this was typical of the ads

that were in circulation:

What a concept! A toy that was marketed EQUALLY to both boys and girls! A

toy that was ASSUMED to appeal to both boys and girls!!! A toy that was, for

all intents and purposes, the holy grail of toys sought after by enlightened

parents and educators—the

gender-neutral-everybody-can-love-it-creative-and-educational-toy!

My, my how times have changed....

As I have

watched Legos change over the last 36 years, it has been simultaneously

fascinating, disturbing, fun, and aggravating to see how the brand has changed

their marketing, meaning both advertising and packaging. Tracking this

progression provides an interesting insight into American (and western

European) cultural attitudes. The overt representation in Lego of both race and

gender, along with the more subtle cues regarding class and ability, has

evolved, and not always for the better. And, with every iteration, I find

myself increasingly ambivalent about the product, and about what it says about

the messages we convey to children about imagination and identity.

Certainly,

the color coding has a lot to do with this. About twenty years ago, Lego saw

their market share dropping, and realized that fewer girls were playing with

them. So their response was to make pink and purple Legos. That didn’t work so

well. Girls still were staying away from them. By focusing on the colors, the

company seemed to overlook the fact that, perhaps, girls weren’t playing with

them because almost all of their

advertising only showed boys playing with them. In addition, their target

demographic had shifted away from young children, and their marketing and

product development was increasingly directed at adolescent boys, coinciding

with a product strategy that leaned heavily on tie-ins with movies that were

also directed at adolescent boys (and young men), such as Star Wars (few women),

Pirates of the Caribbean (one woman), Indiana Jones (one woman), Lord of the

Rings (two women), Harry Potter (few women), and comic books (a couple of

women). If girls don’t see themselves in these character-specific sets, why

would they be inclined to play with them?

And that’s

the biggest change of all—the characters and personalities (aka “minifigs”).

Until the late 1980s, most Lego minifigs had the basic, non-descript face:

With this minimalist face, any child could, potentially, project any character, of any gender, onto the figure (a little more about possible limitations on this in a bit). But once the movie tie-ins began to appear, they were accompanied by the “themed” sets (e.g., space, castle, pirates, city, ocean, polar, etc.), and together, the minifigs took on more specific “character” attributes:

The gender

coding of these figures is pretty obvious. Male figures have facial hair and

often snarling expressions, while females have eyelashes, eye shadow, and

lipstick. And long hair. Because, apparently, this is how we teach our children

to identify gender—solely based on stereotypical, limited representations. And

there has always been far more “male” figures than “female” in these sets. And

it is certainly possible to change the hair that attaches to the top of the

heads, but children are pretty good at recognizing whether two attributes

“match” (so putting Wyldstyle’s streaked high pony tail on a figure with a

mustache doesn’t pass muster for many kids). This identification of gender

based on these two single attributes (hair and facial elements) is so embedded

in our culture that young children learn to default to it even when it doesn’t

reflect the reality in their immediate environment—for example, if you ask a

group of four year olds how you can tell if someone is a boy or girl, they will

almost always respond that, “boys have short hair and girls have long hair,”

even if they are looking right at a female teacher with short hair (I’ve even

heard this response spoken by a boy who, himself, had long hair, looking right

at me, with my very short hair). And if you give them a Lego head, unattached

to a body and without hair, they will also tell you, without hesitation, that a

face with eyelashes and red lips is a girl, while both faces with facial hair as well as faces with the non-descript

features are almost always identified as boy.

And this is

a critical point in this discussion: when figures are not visually coded as

specifically female, children will almost unanimously assume them to be male.

In other words, in our culture, there is, in a practical sense, no longer such

a thing as a “generic” Lego figure, because maleness

is the default. This was true of the culture years ago with the early Lego

figures as well, but there was much more room for children to explore and

ascribe other identities to the figures because girls were included in the equation to a much greater degree. By

showing girls in the ads and the packaging on an equal footing with boys, their

participation was assumed, and so their representation in the “generic” figures

was an easier line to cross.

So, in

response to concerns raised by girls (and parents and teachers) about lack of

representation, and hoping to boost their market share and increase sales, Lego

decided to include girls by making the figures more “girly.” They still didn’t

include them much in advertising of the mainline Lego themed sets and movie

tie-ins, though. When this strategy didn’t really work to increase sales to

girls, they decided to create a line specifically aimed at girls, not just with

pastel colored blocks, but with storylines and completely new figure styles.

I’m referring, of course, to the “Friends” line:

Now, no one

would ever suggest that traditional Lego figures are in any way proportional or

anatomically representational, but that’s part of what gave them imaginative

potential. But the design of these new figures is troubling in that they are

attempting a more accurate physical form (shaped legs and feet; longer legs and

neck; arms more proportional to the body; suggestion of a bust; and a shaped

head with dimensional and detailed features), but are defining that form with proportional

choices that reflect problematic body image types: long legs, thin torso and arms,

and weirdly large head and eyes above a tiny button nose and thin-lipped mouth.

And the age

range printed on the box (along with the breast bumps on the figures) speaks

volumes about who the target audience is here: girls between 6 and 12 years

old, who are at a particularly impressionable point in terms of body awareness

and social expectations. And who, not coincidentally, have more disposable

income in their own control than younger children.

The Friends

figures are also accompanied by artistic renderings on the packaging that is

very different from all the other Lego lines:

These images

are not recreations of movie characters, but are extended interpretations of

the minifigs. The minifigs are still limited in body position and “attitude,”

but the packaging imbues these characters with plenty more. The jutting hip,

the tilted head, the arm position—all reflect the current cultural emphasis on

a specific type of heightened femininity that permeates a child’s world.

Please

understand that I am not suggesting that there’s anything wrong with being a

“girly girl,” as long as that’s the person that you are. But I am suggesting

that this is one more way that we are limiting the expectations and

possibilities for girls to develop a sense of self that is dependent on their

own agency and personality, not on the overwhelming pressure of cultural

images.

And this, my

friends, is why I really want to love the “female scientists” that Lego

recently released, but find myself, once again, ambivalent about the execution.

Look at

that! She doesn’t have long hair! Well, it’s not exactly short, either, but

okay. But she still has those lipstick lips and those mascara eyes. And, just

to make sure we know she’s smart, being a scientist and all, she gets glasses,

too. Or, if chemistry isn’t your thing, you might want to be an

astronomer/astrophysicist:

Whew! I was

worried there for a minute that female scientists couldn’t have long hair! At

least she has it safely bunned up on top of her head. And, just in case you don’t

catch the clues from the eyes and mouth, this one has a jaunty, fashionable,

pink scarf.

I know, I

know, many of you are shaking your head and suggesting that I am over thinking

it (that happens to me a lot), and pointing out that these new science figures

are selling like hotcakes (which they are, apparently, so much so that they’re

getting hard to find), so just stop being critical and accept that girls like

them because now they can imagine themselves as more than Friends or

accessories. (And I haven’t even brought up the whole “race, class, and ability”

thing, which would require another complete post. Maybe another time.)

I’d love to

not have to think about it so much. But I can’t. Not completely. Of course

there are benefits to this (did I mention my ambivalence?), but I still just

can’t get past those faces, and I still am uneasy about the cultural imagery

that is being perpetuated here. I just can’t help but think that girls are

smart enough, and imaginative enough, to be able to see themselves in a toy by

adding them to the marketing, and that every child’s gender development process

could be enhanced by more open-ended choices. In other words, offer the amazing

array of “outfits” and “hair” possibilities, but keep the faces neutral. No

mascara, no lip stick, no beards or mustaches, no snarling expressions—just dots

for eyes, the suggestion of eyebrows, and a simple smile. Kids will fill in the

rest.

(copyright note: some of the images above are taken from internet sources; others are photographs taken by me of products on store shelves)