Advice, reflections, and humor around issues impacting our children, and for those of us who work with them, cherish them, and laugh with them. For early childhood teachers, caregivers, administrators, educators, parents, and anyone who invests in the care and education of young children.

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Kid Considerations: Female Lego Scientists

Kid Considerations:

I Really Want to Like the Female

Lego™ Scientists, But....

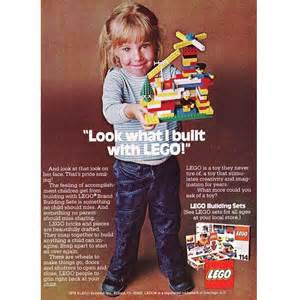

Before I go

any further, let me just make one thing clear—I LOVE Legos! Even though they were available in this country by the

time I was born (and no, you don’t need to know exactly when that was...), they

hadn’t really “caught on” with wide distribution, so, in other words, I never had any as a kid. When I started

teaching (WAY back in the dark ages...1978, that is...), Lego was one of the

toys that fueled my second childhood. At that time, this was typical of the ads

that were in circulation:

What a concept! A toy that was marketed EQUALLY to both boys and girls! A

toy that was ASSUMED to appeal to both boys and girls!!! A toy that was, for

all intents and purposes, the holy grail of toys sought after by enlightened

parents and educators—the

gender-neutral-everybody-can-love-it-creative-and-educational-toy!

My, my how times have changed....

As I have

watched Legos change over the last 36 years, it has been simultaneously

fascinating, disturbing, fun, and aggravating to see how the brand has changed

their marketing, meaning both advertising and packaging. Tracking this

progression provides an interesting insight into American (and western

European) cultural attitudes. The overt representation in Lego of both race and

gender, along with the more subtle cues regarding class and ability, has

evolved, and not always for the better. And, with every iteration, I find

myself increasingly ambivalent about the product, and about what it says about

the messages we convey to children about imagination and identity.

Certainly,

the color coding has a lot to do with this. About twenty years ago, Lego saw

their market share dropping, and realized that fewer girls were playing with

them. So their response was to make pink and purple Legos. That didn’t work so

well. Girls still were staying away from them. By focusing on the colors, the

company seemed to overlook the fact that, perhaps, girls weren’t playing with

them because almost all of their

advertising only showed boys playing with them. In addition, their target

demographic had shifted away from young children, and their marketing and

product development was increasingly directed at adolescent boys, coinciding

with a product strategy that leaned heavily on tie-ins with movies that were

also directed at adolescent boys (and young men), such as Star Wars (few women),

Pirates of the Caribbean (one woman), Indiana Jones (one woman), Lord of the

Rings (two women), Harry Potter (few women), and comic books (a couple of

women). If girls don’t see themselves in these character-specific sets, why

would they be inclined to play with them?

And that’s

the biggest change of all—the characters and personalities (aka “minifigs”).

Until the late 1980s, most Lego minifigs had the basic, non-descript face:

With this minimalist face, any child could, potentially, project any character, of any gender, onto the figure (a little more about possible limitations on this in a bit). But once the movie tie-ins began to appear, they were accompanied by the “themed” sets (e.g., space, castle, pirates, city, ocean, polar, etc.), and together, the minifigs took on more specific “character” attributes:

The gender

coding of these figures is pretty obvious. Male figures have facial hair and

often snarling expressions, while females have eyelashes, eye shadow, and

lipstick. And long hair. Because, apparently, this is how we teach our children

to identify gender—solely based on stereotypical, limited representations. And

there has always been far more “male” figures than “female” in these sets. And

it is certainly possible to change the hair that attaches to the top of the

heads, but children are pretty good at recognizing whether two attributes

“match” (so putting Wyldstyle’s streaked high pony tail on a figure with a

mustache doesn’t pass muster for many kids). This identification of gender

based on these two single attributes (hair and facial elements) is so embedded

in our culture that young children learn to default to it even when it doesn’t

reflect the reality in their immediate environment—for example, if you ask a

group of four year olds how you can tell if someone is a boy or girl, they will

almost always respond that, “boys have short hair and girls have long hair,”

even if they are looking right at a female teacher with short hair (I’ve even

heard this response spoken by a boy who, himself, had long hair, looking right

at me, with my very short hair). And if you give them a Lego head, unattached

to a body and without hair, they will also tell you, without hesitation, that a

face with eyelashes and red lips is a girl, while both faces with facial hair as well as faces with the non-descript

features are almost always identified as boy.

And this is

a critical point in this discussion: when figures are not visually coded as

specifically female, children will almost unanimously assume them to be male.

In other words, in our culture, there is, in a practical sense, no longer such

a thing as a “generic” Lego figure, because maleness

is the default. This was true of the culture years ago with the early Lego

figures as well, but there was much more room for children to explore and

ascribe other identities to the figures because girls were included in the equation to a much greater degree. By

showing girls in the ads and the packaging on an equal footing with boys, their

participation was assumed, and so their representation in the “generic” figures

was an easier line to cross.

So, in

response to concerns raised by girls (and parents and teachers) about lack of

representation, and hoping to boost their market share and increase sales, Lego

decided to include girls by making the figures more “girly.” They still didn’t

include them much in advertising of the mainline Lego themed sets and movie

tie-ins, though. When this strategy didn’t really work to increase sales to

girls, they decided to create a line specifically aimed at girls, not just with

pastel colored blocks, but with storylines and completely new figure styles.

I’m referring, of course, to the “Friends” line:

Now, no one

would ever suggest that traditional Lego figures are in any way proportional or

anatomically representational, but that’s part of what gave them imaginative

potential. But the design of these new figures is troubling in that they are

attempting a more accurate physical form (shaped legs and feet; longer legs and

neck; arms more proportional to the body; suggestion of a bust; and a shaped

head with dimensional and detailed features), but are defining that form with proportional

choices that reflect problematic body image types: long legs, thin torso and arms,

and weirdly large head and eyes above a tiny button nose and thin-lipped mouth.

And the age

range printed on the box (along with the breast bumps on the figures) speaks

volumes about who the target audience is here: girls between 6 and 12 years

old, who are at a particularly impressionable point in terms of body awareness

and social expectations. And who, not coincidentally, have more disposable

income in their own control than younger children.

The Friends

figures are also accompanied by artistic renderings on the packaging that is

very different from all the other Lego lines:

These images

are not recreations of movie characters, but are extended interpretations of

the minifigs. The minifigs are still limited in body position and “attitude,”

but the packaging imbues these characters with plenty more. The jutting hip,

the tilted head, the arm position—all reflect the current cultural emphasis on

a specific type of heightened femininity that permeates a child’s world.

Please

understand that I am not suggesting that there’s anything wrong with being a

“girly girl,” as long as that’s the person that you are. But I am suggesting

that this is one more way that we are limiting the expectations and

possibilities for girls to develop a sense of self that is dependent on their

own agency and personality, not on the overwhelming pressure of cultural

images.

And this, my

friends, is why I really want to love the “female scientists” that Lego

recently released, but find myself, once again, ambivalent about the execution.

Look at

that! She doesn’t have long hair! Well, it’s not exactly short, either, but

okay. But she still has those lipstick lips and those mascara eyes. And, just

to make sure we know she’s smart, being a scientist and all, she gets glasses,

too. Or, if chemistry isn’t your thing, you might want to be an

astronomer/astrophysicist:

Whew! I was

worried there for a minute that female scientists couldn’t have long hair! At

least she has it safely bunned up on top of her head. And, just in case you don’t

catch the clues from the eyes and mouth, this one has a jaunty, fashionable,

pink scarf.

I know, I

know, many of you are shaking your head and suggesting that I am over thinking

it (that happens to me a lot), and pointing out that these new science figures

are selling like hotcakes (which they are, apparently, so much so that they’re

getting hard to find), so just stop being critical and accept that girls like

them because now they can imagine themselves as more than Friends or

accessories. (And I haven’t even brought up the whole “race, class, and ability”

thing, which would require another complete post. Maybe another time.)

I’d love to

not have to think about it so much. But I can’t. Not completely. Of course

there are benefits to this (did I mention my ambivalence?), but I still just

can’t get past those faces, and I still am uneasy about the cultural imagery

that is being perpetuated here. I just can’t help but think that girls are

smart enough, and imaginative enough, to be able to see themselves in a toy by

adding them to the marketing, and that every child’s gender development process

could be enhanced by more open-ended choices. In other words, offer the amazing

array of “outfits” and “hair” possibilities, but keep the faces neutral. No

mascara, no lip stick, no beards or mustaches, no snarling expressions—just dots

for eyes, the suggestion of eyebrows, and a simple smile. Kids will fill in the

rest.

(copyright note: some of the images above are taken from internet sources; others are photographs taken by me of products on store shelves)

Friday, September 26, 2014

Kid Policy: Scapegoating the Common Core

Kid Policy:

Scapegoating the Common Core

A

Facebook friend of mine, who regularly (and, in my opinion, justifiably)

expresses her frustration with the amount of homework her first grader has to

confront, recently expressed another frustration: the math worksheet her

daughter had for homework was not well-designed, and its intent was difficult

to decipher. Specifically, there was a word problem that didn’t seem to be

clear regarding whether the purpose was to construct a subtraction problem, an

addition problem, or identify a place value relationship. Her Facebook post was

asking for help figuring out what was expected.

It

didn’t take many comments before someone growled about the “Common Core” and

how it’s ruining education. Several others chimed in on this train of thought.

I have witnessed this response many times in the last few years, as parents and

educators cope with their dissatisfaction with mountains of homework,

struggling teachers, disconnected administrators, and rigid standardized

testing expectations. Inevitably, these concerns generally wind up focused on

the Common Core as the enemy. The problem, however, is that the Common Core

isn’t the problem.

These

indictments of the Common Core (technically, they are officially called the

“Common Core State Standards,” since

they were developed by representatives from the National Governors Association

Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School

Officers (CCSSO)) are often misguided and misinformed, and are grounded in the

belief that the federal government is, once again, interfering in our lives, telling

us what to do, and supporting private (often “charter”) schools at the expense

of public schools. This viewpoint is encouraged by journalists and pundits from

both sides of the aisle who perpetuate the notion that the Common Core creates

unrealistic and burdensome expectations on students, especially young students.

Here’s

the thing, though—if you actually take the time to read any of the Common Core

standards, you will notice four specific things that seem to get lost in this

conversation:

- The Common Core is not a curriculum. There are some model curricula that have been developed to provide examples of ways to implement some of the standards, but these are models only. There is no requirement that any state, district, school, or individual teacher use the model.

- The Common Core does not specify HOW to teach any specific standard. See the first point above. The Core does not, can not, and will never dictate what type of philosophy or pedagogical approach districts or teachers have to use.

- The Common Core has nothing to do with how much homework your child is assigned. See the previous two points above. The development and implementation of curriculum, homework, testing, and even recess, is determined by the state, the district, the school administrators, and (increasingly rarely), individual teachers.

- The Common Core is not required to be adopted by individual states unless the state is seeking to supersede (or circumvent) the requirements of No Child Left Behind. The Core Standards were originally conceived of, and developed by, individual states wishing to either raise the standards above what was set by NCLB, or to be granted a waiver from NCLB.

Again,

the Common Core isn’t the bogey man—it is a set of research-based standards

that simply attempts to organize basic skills and content into a practical

sequence that is intended to align and clarify the patchwork of quality

standards that has historically varied widely from state to state (follow this link for a brief, reasoned explanation of the process, or this link to go to read about “myths versus facts”). There is certainly a

compelling discussion to be had regarding the politics, adoption, and

implementation of the Common Core by individual states, and the affect that

this process has had on teachers, students, and families, but unless we make

ourselves familiar with the actual content of the Common Core documents, it is

difficult to elevate such a discussion beyond rancorous politics and

inflammatory rhetoric.

So,

who should we direct our anger at when a seven-year old child routinely comes

home with 2 hours’ worth of poorly designed worksheets? First of all, yelling

at the teacher won’t help. Many teachers are as frustrated as parents with

current trends in classroom practice and curriculum development, which often

dictates rigidly scheduled instruction and intense pressure to standardize

teaching along with content/skill standards for children. It is also pointless

to rail at the federal government—the Common Core is not mandated or

administered by the federal government, though its implementation is, in some

cases, tied to federal guidelines.

I

think our anger needs to be directed at what lies at the heart of the

disempowerment of teachers, the pressure on districts and administrators to

prove their efficacy based on test results, the disregard for family

interactions, and the objectification of children as raw material—and that is

the corporatization (and monopolization) of education. To point to the most

compelling and far-reaching example of this trend: It is no coincidence that the

dominant corporation that is working toward a near monopoly throughout the

pre-K through college schooling experience, Pearson Education, has convinced

states to adopt their assessment tools; has lobbied districts and private

schools to purchase their scripted curriculum packages to teach to those tests;

has acquired several publishing divisions to develop and sell those packages

(such as Scott Foresman, Penguin, Puffin Prentice Hall, Addison Wesley, and

Silver Burdett); has reached into all facets of teacher education and

preparation to produce teachers who will be proficient at using only their

materials; and has sponsored and conducted much of the (little bit of) research

that has been done on the effectiveness of those materials.

It

is also important to understand that Pearson was not historically even

interested in education until the 1980s, suggesting that their current

iteration did not grow from a rich history of education experience and passion,

but simply from a desire to maximize profit by exploiting a segment of a market

that was limited until education became a viable business proposition in the

late 1990s. Even their own description of their beginnings from their website

notes their late entry into education:

“Pearson’s roots are grounded in global innovation that transforms

the landscape and stands the test of time. Our London-based company started in

1844 as a construction company building such noteworthy projects as the Sennar

Dam in Egypt and the Manhattan tunnels in NY. We turned to media in the UK in

1921 and diversified into global book publishing in 1971 and education in the

1980s, dabbling in numerous industries along the way.

Then, in 1997, everything changed. In a bold and somewhat

controversial move, Marjorie Scardino was hired as one of the first female CEOs

of a major FTSE company. The decision ushered in an even bolder aspiration: to transform education globally in order to improve people’s lives

through learning.” (http://www.pearsonk12.com/meetus.html)

A

company that “dabbles” until it finds a profitable direction is not a company

that is passionate about education. They are passionate about profit, and

“transform[ing] education globally” is not “in order to improve people’s lives

through learning,” but to improve the bottom line for Pearson’s board and

stockholders.

The

only real indictment of the Common Core in this picture is that it has enabled

Pearson to streamline their products by giving them a single set of standards

to use as their alignment tools, rather than producing multiple products that

respond to different standards in different states, which has facilitated this

corporate approach to education.

So,

what to do the next time your kid brings home that mountain of homework that

doesn’t make sense to you? After you take a deep breath, ask the teacher what

curriculum package her/his school is using, and whether he/she has much input

into its implementation. There’s a good chance that your child’s teacher is as

frustrated and disempowered as you, and an equally good chance that Pearson is

somewhere in the picture. Then ask the school administration why they chose

that curriculum, and ask for the research that supports their approach. If the

school doesn’t use a scripted curriculum, then ask the teacher the reasoning

behind the assigning of a heavy homework load, and be prepared to challenge

that reasoning by familiarizing yourself with the work of Alfie Kohn here, or the position

taken on Great Schools.org here,

which notes that, “In fact, for elementary school-age children, there is no

measureable academic advantage to homework.” (You can also point out that a

Canadian couple successfully sued to have their children exempted from all

homework, arguing that there is no compelling evidence that homework helps learning,

as explained in this article.)

But

bashing the Common Core? That’s not going to help. And it only serves to divert

attention away from the profit-monster that is driving corporate U.S. education

policy. And no, I’m not a raging-socialist-anti-capitalist-commie who is

suggesting that companies shouldn’t make a profit. I’m just an experienced,

informed, concerned educator (and parent) who believes that they shouldn’t do

it by turning children into manufactured products of an educational machine.

Call me crazy....

Monday, September 15, 2014

Kid Considerations: Starting Over

Kid Considerations:

Starting Over—Taking My Own

Advice

Two of my earlier blog posts focus on helping children with separation anxiety and with the transition from preschool to kindergarten (“Lift and Separate: Separation Anxiety in Young Children”; and “Movin’ On Up: Transitioning to Kindergarten, with Tips for Easing Anxiety,” both from May 19). It has been a while since I have managed any new blog posts, and the reason for that is also the reason that I realized I needed to revisit those earlier posts and heed my own words.

After a career spanning 36 years as a preschool teacher and administrator, I recently closed the preschool program that I founded 28 years ago. This was a difficult decision to make, but it was the right one. As I sent off my final group of kids to the adventure of kindergarten, I immersed myself in the process of sorting, organizing, storing, liquidating, and disposing of the wealth of materials, supplies, and furnishings that we had accumulated over those years. This was a huge, daunting task, and one that pretty much consumed most of my time for over a month, culminating in a public auction that was both gratifying and difficult. After deciding what to take home (items both sentimental and practical), what to keep in storage (business records and picture books), or what I would need to have to continue providing professional development (teaching materials and, again, picture books), I watched as a sizable group spent 3 ½ hours on a steamy summer evening scrutinizing, considering, and bidding on the rest.

When the dust had settled, 90% of what we had put up was in the hands of others. Many of the bidders that evening were teachers or program owners/administrators, several were parents or grandparents, and the rest were mostly people who make a living selling good quality used toys and materials at flea markets. I was especially pleased to see so many of our educational materials find their way into the other preschool and care programs, including the hundreds of picture books that were still on the shelves.

As I sit here now, I can imagine the fun and learning that children are experiencing with the same items that our kids used for so long, and the separation is a little easier. There have been many times in the last several weeks when I have stopped to remember the advice I have given to countless parents when their child is facing a major transition, whether it’s going to kindergarten, moving to a new house, welcoming a new sibling, or saying good bye to someone who has passed on. The primary point of that advice has always been that change in difficult, but it is important to convey to your child that you believe he/she is strong enough manage that change, and to help them through it by providing love, support, and, most importantly, as much consistency as possible.

I am certainly no stranger to change, but this particular change was one of the more challenging I have confronted. Just as a child entering kindergarten experiences excitement and uncertainty, sadness and joy, and fear and hope, I, too, was experiencing many of the same feelings. I am fortunate to have many wonderful family members and friends to provide the love and support, but I realized that it would be up to me to provide the consistency. Since I am not stepping immediately into a full time job at another location, for me, consistency referred to a few key points: developing a routine and sticking with it; creating a space at home dedicated to the work I will be doing (i.e., writing, research, and the creation of professional development workshops); and being sure to remain mindful of and attentive to my emotional space.

Now that the school has been closed, the remaining stuff has been disposed of, given away, or stored, and the keys have been turned in, I am ready to begin kindergarten again with my eyes and heart open.

Monday, July 21, 2014

Kid Considerations: Children are NOT Collateral Damage

Kid Considerations:

Children are NOT “Collateral

Damage”

This

post will be a relatively short one, and a decidedly opinionated one. The

events in Gaza trigger passionate responses on all sides. I’ve tried very hard

to understand and have compassion for the arguments from both the Israeli and

the Palestinian governments and citizens, in both a contemporary as well as an

historical sense. I do not support suicide bombers whose targets are

indiscriminate, even if they are fighting for their homeland, any more than I

support firing rockets at targets that are “supposed” military locations

without 100% confirmation. I support everyone’s right to defend themselves from

military and sectarian violence.

But

here’s the bottom line: There is no excusing the actions of any government or

their military that has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of civilians,

including dozens of children. I do not support any military action that

considers children to be acceptable “collateral damage.” When you

decide that children are expendable, then I don’t care who you are, I don’t

care what your religious beliefs are, I don’t care what has been done to you in

the past, I don’t care about any claims about media bias...I care about the

children. And until you stop killing them, you will have no compassion from me.

Parents,

if your child is old enough to understand these news reports and is asking

questions about it, be careful how you explain this to them. Their questions

are likely rooted in fear of losing you, or of a growing understanding of their

own potential mortality. Find the delicate line between recognizing the

realities of the situation and reassuring children that they (and you) are

safe: explaining war to children who have never lived amidst such violence is

challenging, and it is even more challenging to try to explain it to them

without burdening them with the fear and hatred that leads to such violence.

Unfortunately, this is not limited to far away wars in far away countries—sadly,

the children of Chicago are asking these same questions. Wherever you are, name

the violence, understand the violence, and condemn the violence. And hold your

children a little closer.

Sunday, July 6, 2014

Kid Considerations: I'm Leaving Without You

Kid Considerations:

“I’m Leaving Without You”: The

Four Worst Words an Otherwise Loving Parent Can Use

During a recent vacation, I was at a bucolic tourist

destination that experiences heavy family attendance during the summer.

Throughout the day, I heard numerous examples of the usual parental commands

and pleas that are a natural part of family travel, such as “We’re leaving

NOW!”; “Put that down and come here!”; “No, we’re not staying a few more

minutes”; “I know I said you could play on that before we leave, but someone

else is there and we’re not waiting....”; etc. I also heard more than a couple

of times the four most devastating and potentially damaging words a parent (or

grandparent) can use: “If you don’t come right now, I’m leaving without you!”

As a parent, I have traveled with a young child, and I know

how challenging it can be when the day is long, the environment is stimulating,

and the temperature is punishing. And I know the feeling of impatience and

frustration even in a non-vacation daily routine when I recognized that we had

to be somewhere, and needed to leave now

to get there on time, but my daughter didn’t share my imperative to get a move

on. And I’ve experienced the aggravation of wanting to pick up my child at the

end of a long, tiring day (for both of us) and get home, while she was not

quite ready to separate from her friends.

No matter how irritated, stressed, or annoyed I became, I

never ever ever once threatened to

leave her behind. And our program staff know, if they hear a parent make such a

statement at pickup time, that they are to immediately intervene, assuring the

child that her/his parent is NOT going to leave them behind. Even if doing so

makes a parent angry, it is important that the children in our care feel safe,

loved, respected, and wanted—four

things that parents should be doing in their interactions as well.

There are two main reasons that making this threat is not

just poor parenting, but has potentially serious long term consequences as

well:

1. By the time a

child is 4 or 5 years old, he/she will have figured out that you are lying.

Once that happens, you have, perhaps irrevocably, shattered their trust in you.

You have given them every reason to question everything you tell them. And if

they can’t trust you to be honest, they will have trouble trusting you to look

out for them. They will also have learned that lying is a perfectly acceptable

tactic to get what you want.

2. And most importantly of all: Even more than betraying

their trust, threatening to leave manipulates one of the most primal fears a

child can have—the fear of abandonment. And

that’s why parents do it—because it works. If children didn’t harbor a

fundamental fear of losing their parents and family, they wouldn’t care. The

reason it works is exactly the reason you should never do it. Ever.

So what do you do when you need/want to leave and your child

doesn’t? First of all, establish a pattern early on of never making a promise

OR propose a consequence unless you can and WILL follow through. If you create

a firm foundation of reasonable expectations and mutual trust, then you won’t

need to manipulate fears with lies and threats to get a child to behave. Once

you have established this pattern, understand that young children simply don’t

experience time with the same sense of purpose that adults do, but there are things you can do to help with the process:

- Make sure you have explained clearly to your child why it is important to leave at a particular time;

- Whenever possible, tell your child at least 5 or 10 minutes before it is time to leave that they will need to stop what they are doing, and how long they have left;

- Remind your child what the expected behavior will be when it is time to go (e.g., “when it’s time to go, you need to stop what you’re doing and come along without an argument”);

- Validate your child’s feelings about leaving while reinforcing the actions that you will take (“I know you are having fun and are disappointed/angry/sad that we have to leave, but that doesn’t change the fact that we will be leaving in five minutes”);

- And when it is time to leave, leave, even if it means struggling to stay calm while you pick up your screaming child and carrying her/him out the door. Even if you are in a public place, if you allow your child’s tantrums to delay your departure (in other words, if you give in and stay longer because you are afraid of being embarrassed by her/his behavior), then he/she will learn that tantrums work.

Be firm. Be fair. Be calm. Be loving. Be honest.

Thursday, June 12, 2014

Kid Smiles: Melon Did It

Kid Smiles:

Melon Did It: Imaginary Friends, Stories and Lies, and Accepting Responsibility

I

knew a three-year old girl who, any time she did something she wasn’t supposed

to (which was fairly often), would announce, “Melon did it!” Melon, of course,

was her imaginary friend. Sometimes Melon was a good companion, engaging in

thoughtful conversation, but, most often, Melon was the scapegoat. Melon didn’t

seem to mind much.

I

also remember a four-year old boy who once broke something on the playground.

Even though he was the only one in the area, and despite the fact that a

teacher had actually seen him break the toy, when I asked him why he did that,

he said, “because....wait, I didn’t do it...” When I asked him who did do it,

he looked around, then innocently said, “how about Colby?” Now, ordinarily,

Colby would have been a viable suspect, but on this day, he wasn’t even at

school, giving him a solid alibi.

Both

of these memories make me smile. They are also both really good examples of the

way preschoolers will naturally try to negotiate the truth. It’s not

pathological lying (yet), it’s simply coming to a developmentally appropriate

understanding of the relationship between reality and fantasy. It’s also part

of the process of learning to accept responsibility for our actions and

behaviors.

It’s

sometimes difficult for adults to figure out how to respond to these narrative

explorations. We want to encourage imagination, and we often are amused by the

clumsy trek through the truth that preschoolers pursue. But while they are on

this journey, it’s important to help them recognize the difference between the

fun and positive use of imagination, and the problematic manipulation of truth

to deflect responsibility or to get what you want. There’s nothing wrong with

naming that difference, and naming it makes it easier for children as young as

three to understand: using imagination to tell stories (or to have imaginary

friends) is fine, as long as the people you’re telling them to know that

they’re stories, but making things up that you know are false and trying to get

others to believe you is lying. It really is that simple (but I’m sure we all

know some grown ups who still struggle with this concept).

Young

children lie for a variety of reasons. Probably chief among them is to deny

wrongdoing and get out of trouble (the function of Melon and Colby), but

children will sometimes lie just to see what happens, or to try to reconstruct

their world in ways that make them feel better. An example of the “just to see

what happens” tactic is the little girl who, with somber earnestness, told us

that her mother couldn’t come to pick her up that day because she had been in a bad car

accident and was in the hospital. We were all appropriately concerned and

confused, because we hadn’t heard anything about it, but things were cleared up

when Mom walked in the door that afternoon, safe and sound. When we asked the

girl why she told us that, she said, “I don’t know.” And she didn’t know. She

was trying it out. An example of a child reconstructing the world to make

himself feel better was the little boy who, after having experienced some

meaningful trauma, insisted on calling his adoptive parents “Nala” and

“Mufasa,” and wanted everyone to call him “Simba.” For this young boy, the

simple reality was that, for him at that moment in his life, reality was

challenging, and his healing involved a harmless construction of a world of

strength, perseverance, connection, and heroism to get him through. This lasted

for a couple of months, until we all recognized that reality was once again, for him, a safe place to be.

If

you value honesty and integrity, then you will help the children in your life

understand why those concepts are important. Adults will often excuse lying as

“harmless fantasy,” or with the belief that children “are just too young to

know any better.” If children are old enough to have the vocabulary to create

stories, they are old enough to begin to understand morality and ethics, and

the difference between lying and storytelling. But the only way they can learn

the social significance of these concepts is if adults take the time to name

the problem, set clear and consistent expectations and consequences, and

explain what the choices are. One of the best books to help children (ages four and up) with this

concept is Evaline Ness’s Sam, Bangs, and

Moonshine. This book tells the story of a little girl, Sam, whose elaborate

stories ultimately cause serious injury to her best friend, Thomas, and to her

cat, Bangs. Sam’s stories begin as a way to help her cope with the loss of her

mother, but evolve into an escape from reality that is no longer healthy for

her or for those around her. Her father explains to her the difference between

“real” and “moonshine,” and helps her to accept responsibility for the

consequences of her actions.

And

that really is the point: Sam’s father doesn’t discourage her from telling

stories, but insists that she be clear with others (and with herself) that she

is making it up. Similarly, we welcomed Melon at school, but insisted that she not

be blamed for her friend’s behavior. It was only fair.

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

Kid Tips: Itching to Know

Kid Tips:

Itching to Know—Being Poison Ivy

Literate

I

know, I know...so far, all of my posts have been about behavioral issues, or

developmental considerations, or thoughtful reflections on cultural issues and

influences...so what’s with the poison ivy?

Well,

it’s almost summer here in the Midwest, and summer means poison ivy, and poison

ivy means misinformation, myth, and misery for 70-75% of the population,

including kids. This is one of those topics that I have learned a LOT about

through painful necessity. I first had a serious poison ivy reaction when I was

five years old, which landed me in the hospital for nearly a week with a solid

mass of blistering pustules covering my entire thigh. As a teenager, I was

bedridden for several days after I had been at a friend’s house where they were

burning brush that included poison ivy, and the aerosolized oil basically

coated my head, neck, arms, and hands—my eyes were swollen shut, my upper lip

was about three times its normal size, my ears stuck out from the layers of

rash behind them, and I couldn’t use my hands normally because of the huge

blisters in between my fingers.

My

apologies for the graphic description, but the point is...I know what I’m

talking about. When parents come to me with concerns that their child got

poison ivy from our back yard, I reassure them that we are VERY careful about

making sure we clear any poison ivy from the fence line, and then I fill them

in on what they will need to know for the rest of their child’s life, since poison

ivy allergies persist (and sometimes get worse) over time. I am not a physician

or a botanist, but here is what I have learned through my experiences over the

last 50 years (if anyone has any further information, or if you believe

anything I have said below is incorrect, please let me know—I do not claim to

have all the answers):

ASSUMPTION #1: YOU CAN

SPREAD POISON IVY BY SCRATCHING. Partly true, but misleading. The rash is caused by

your body’s histamine reaction to the oil

that is part of the plant. This oil is known as urushiol, and is contained not only in poison ivy, but also in

poison oak, poison sumac, and in smaller amounts in other plants such as mango

trees, pistachio trees, cashew shells, and gingko biloba. Once the oil contacts

the outer skin layer, your body begins to react. For people with serious

sensitivities (like, for example, me), that reaction can be almost immediate

when the urushiol density is significant. If your immune system triggers

itching before you have removed the oil, the action of scratching MAY spread

the oil over a larger area. Once you

have washed off the oil, however, you cannot spread it anymore simply by

scratching. Most importantly, you CAN NOT spread poison ivy by scratching

open the blisters, and no one else can “catch” poison ivy from coming into

contact with the fluid in the blisters. The fluid that forms inside the

blisters is NOT urushiol—it is the fluid that is naturally produced by your

body as part of the histamine reaction. The main danger of scratching is not

spreading the allergic reaction, but causing a bacterial infection. As the

blisters open and release their fluid, make sure you keep the area clean and

covered to prevent infection.

ASSUMPTION #2: YOU CAN’T

WASH AWAY THE OIL. False. If you know you have contacted poison ivy, you must thoroughly

wash away the urushiol as soon as possible, before it bonds with the skin layer

(within 10 minutes or so). This can be accomplished with commercial products

(such as Ivy Dry or Zanfel, which can also be used after the urushiol has

bonded), or with COOL/COLD water and soap or common household detergents that

are good at breaking up oil (such as many dish detergents or, my favorite soap

for this purpose, Fels-Naptha, a bar soap that can also be used as a laundry

detergent to remove the oil from clothing—be aware, however, that, since it is very,

very good at breaking up oil, it should probably not be used for routine

bathing, as it will strip your skin of beneficial, natural oils as well). DO

NOT shower or wash with hot or very warm water, as this will open the

pores and make it easier for the oil to penetrate, and can actually spread the

rash by making the oil flow easier.

ASSUMPTION #3: IF I DON’T

TOUCH IT, I WON’T GET IT. False. Big false. In fact, in many cases, initial or subsequent

reactions are not from the plant itself, but from pets or clothing that have

the oil on them. We had a student several years ago whose parents were

convinced that he was repeatedly getting poison ivy at school, because they had

not been in ivy-infested areas for several weeks, but their son kept getting

new rashes. After some questioning, we realized that, several weeks prior (when

he got the first exposure), it had been in an area with lots of poison ivy, and

that, since the initial contact, they had not washed his shoes. He had walked through the field with the poison

ivy, and since they hadn’t washed his shoes, he kept re-contacting the oil

every time he put on his shoes. If you have been exposed, make sure you not

only wash yourself, but also be careful to launder all of your outer clothing, including

your shoes and jackets, with a detergent that will break up oil. If you

can’t launder an item (like hiking boots, for example), clean them as

thoroughly as you can, then wash your hands immediately after you put them on,

or just don’t wear them for several weeks (though urushiol can remain viable

for several months, so exercise caution and continue to wash your hands).

Similarly,

if you take your dog for walks in the woods or fields, or if your dogs or cats

have access to areas where there may be poison ivy, be aware that they can

carry the oil on their fur. If you or someone in your family is allergic, be

sure to give your dog a bath when you return from your walk, and keep your yard

clear of poison ivy.

ASSUMPTION #4: THE BEST

TREATMENT FOR POISON IVY IS CALAMINE LOTION. Hmmm....maybe. Calamine lotion, or other

topical lotions and creams, can help relive the itching for minor reactions,

but if the reaction is moderate or severe, topicals will not be very effective.

In extreme cases, you may need to see a doctor for a prednisone injection to

combat the inflammation and help prevent scarring. For moderate cases, the

thing to keep in mind is that you want to dry

the rash, which will help to alleviate symptoms. There are a variety of

astringent products that can help with this process. My favorite is a powder

called Domeboro solution, which you use by mixing with cool water, then soaking

a washcloth or gauze compress with the solution and applying the compress to

the rash for 10-20 minutes, several times a day. Not only does this help to dry

out the histamine fluids (which is what causes the itching), the cool compress

also soothes the skin and helps make it less miserable. Taking antihistamines

may help a little, but will be limited in their effectiveness. Whatever

approach you take, it generally takes a week or two for the reaction to fully

run its course and for the rash to disappear (it may take longer with severe

cases).

ASSUMPTION #5: YOU CAN ONLY

GET POISON IVY IN THE SUMMER. Definitely false. In fact, poison ivy can be most

potent in the spring, when the plant is coming out of winter dormancy and the

oil is dense and active (think of the way the “sap rises” in maple trees in the

early spring—same idea). Summer drought and heat can “dry up” the vines to a

certain extent, though the oil will still be present. However, even when the

plant is “dormant” (during the winter in cold climates), the oil can still be

present in sufficient quantity to cause a reaction. If you’re one of the 70%

that reacts to urushiol, don’t think you can yank the vines out in the winter

without getting a rash. It may be less potent, but it can still be enough to

cause a rash.

ASSUMPTION #6: IF I’M NOT

ALLERGIC TO IT NOW, I WILL NEVER BE. Dangerously false. As with any other allergy,

repeated exposure, or natural changes to body chemistry over time can lead to

new allergies.

ASSUMPTION #7: ANY PLANT

WITH THREE LEAVES IS POISON IVY. Frustratingly false. There are many plants that

resemble poison ivy, such as maple tree saplings, catalpa tree saplings,

Virginia creeper, box elder, pepper vine, etc. This link provides a lot of

photos of poison ivy and various “impostors”: http://poisonivy.aesir.com/view/picqna.html.

Identifying poison ivy can be confusing, but here are some things to remember:

·

Poison ivy is a vine, not a tree. It rarely grows straight and tall by

itself. It prefers to be anchored to another tree, a rock face, or a wall for

support, but can also grow without support, looking more like a bush or ground

cover.

·

The vine is woody (and sometimes “fuzzy”) on mature plants anchored to

trees, but can be smooth and red or green on new growth.

·

The leaves can be toothed or smooth, but are not usually lobed.

·

The leaves are reddish in the spring, green in the summer, and can be

various shades of orange, yellow, red, or brown in the fall and winter.

·

The center leaf usually is larger than the two side leaves, and the

center leaf almost always grows from a small stem that grows from the end of

the vine, whereas the side leaves grow directly from the vine itself, without a

separate stem.

Bottom

line: if it has three leaves and you’re not sure what it is, don’t touch it.

So,

keep your eyes open, stock up on soap, and good luck!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)